The Maryland Campaign is known primarily (by most) for the Battle of Antietam. However, two battles contested in present day West Virginia played pivotal roles in this campaign. Today we look at the battle of Harpers Ferry.

Lee Assumes Command

Confederate General Joseph Johnston was seriously wounded as the Battle of Seven Pines raged. Following the inconclusive battle, Robert E. Lee was placed in command of the Confederate Army, which he rechristened the Army of Northern Virginia. Never having commanded a large army in the field, Lee immediately formulated an offensive. Lee’s movement resulted in the Seven Days battles, which drove the Union forces from the outskirts of Richmond, saving the Confederate capital. Following a decisive victory in the Battle of Second Manassas, Lee was determined to take the fight to the north. This offensive would later become known as the Maryland Campaign, resulting in the climactic Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest day in American history.+

A battle at Antietam was the farthest thing from Lee’s mind. He had his sights set on the Pennsylvania heartland. He could feed his army and provide some relief to the agricultural regions of northern Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley. Lee wanted to maintain pressure on the disorganized and demoralized Federals and force them to move before they were ready. A great victory on northern soil could provide European recognition and intervention. Lee wanted to play the political card as well. Fall congressional elections were only two months away, and at the time, the Republicans held the majority. Since all appropriations bills originate in the House, if the Democrats regained the majority, there was the potential that they could stop funding the war and negotiate a settlement with the Confederacy. With a southern army in Pennsylvania, the voters could be swayed to vote for the democratic candidates.[1]

On September 4, 1862, the Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River into Maryland near Leesburg and advanced, unchecked, to Frederick. A battle at Harpers Ferry was not a part of Lee’s plans. When the Army of Northern Virginia occupied Frederick, Lee expected that the Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg garrisons would be withdrawn. Lee was wrong. The Federal troops were told to stay put. Dixon Miles commanded the Harpers Ferry Garrison. The last order he received before the telegraph lines were cut told him not to abandon Harpers Ferry. [2]

Col. Dixon Miles (LOC)

Lee Has a Problem

Now General Lee had a problem: a Federal force to his rear. He knew he had to deal with that force before proceeding. Thus, he issued Special Orders 191, perhaps Lee’s most complex orders during the entire war. The army was divided into four parts. Three columns, comprising approximately two-thirds of Lee’s army, under the overall command of General Thomas J. Jackson, were ordered to move on Harpers Ferry. Each column was to travel a different route, facing different obstacles, and arrive at its destination simultaneously, a nearly impossible task. If anybody was up to the task, it was Jackson.[3] A column commanded by General Lafayette McLaws was ordered to take Maryland Heights, a column under General John G. Walker was ordered to take Loudon Heights, while Jackson’s column would take Bolivar Heights. With Longstreet’s command, Lee would move to Hagerstown, which would be the rendezvous point for Jackson’s force sent to capture Harpers Ferry. Hagerstown would then be the springboard for the invasion of Pennsylvania.[4]

On September 8, Colonel Miles began preparing for the defense of Harpers Ferry. Since taking command, he had done very little to fortify the heights despite receiving orders. Major General John Wool had previously instructed Colonel Miles to build a blockhouse on Maryland Heights, construct entrenchments on Bolivar Heights, and lay abatis on Camp Hill. These orders were never acted upon, although Miles did construct a naval battery part way up Maryland Heights and place entrenchments on Camp Hill. On September 12, Brigadier General Julius White abandoned Martinsburg with his two thousand five hundred troops and retreated to Harpers Ferry. The garrison now numbered fourteen thousand troops. White ceded command of the garrison to Colonel Miles.[5]

A week prior, Miles had placed Colonel Thomas Ford (Thirty Second Ohio Infantry) in command of the troops on Maryland Heights. When he arrived at the heights, Ford found no fortifications. He requested artillery to be placed at Solomon’s Gap so his troops could command the position but was overruled by Colonel Miles. Upon making a second request, Ford was denied again. On September 11, McLaw’s men camped in Pleasant Valley (just beyond Maryland Heights), drove in the Federal pickets, and prepared for battle the next day.[6] According to Ford,

“During the night both armies slept on their arms within speaking distance of each other, and certainly not more than one hundred yards apart.”[7]

Late that night, five companies of Colonel Downey’s battalion arrived to reinforce the position. The battle began in earnest at 6:30 a.m. on the following day. After two hours of heavy fighting, the Federals returned to their hastily constructed breastworks. Colonel Eliakim Sherrill, commanding the One Hundred Twenty-sixth New York, was severely wounded during the fighting and carried to the rear. The green troops of his regiment began to panic, and many fled from the field.[8] The remaining Federal troops continued fighting through the afternoon but were soon overwhelmed by the veteran soldiers of William Barksdale and Joseph Kershaw.[9] With Confederates, in great numbers, advancing at his front and believing his left was about to be flanked, Ford ordered the guns to be spiked and dismounted (they never were), and the Federals retreated down the mountain and crossed the pontoon bridge into Harpers Ferry.[10] With Maryland Heights under Confederate control, McLaws placed his artillery. The Federal position was now tenuous at best.[11]

On the morning of June 13, General Walker’s column reached the base of the Blue Ridge opposite Loudon Heights, which appeared empty, and Jackson was three miles south of Bolivar Heights. Loudon Heights was, in fact, open, as Colonel Miles had failed to place any Federal troops there. To be sure, Walker sent Colonel John R. Cooke, his Twenty-Seventh North Carolina, and the Thirtieth Virginia to reconnoiter the summit. Meeting no opposition, they took the heights and held through the night. At dawn, Walker sent his guns (three Parrott guns and two rifled pieces to Loudon Heights and put them in position.[12]

Surrounded

Miles now found himself in dire straits. He was surrounded on three sides, but he refused to surrender. The Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers separated Maryland Heights and Loudon Heights, respectively, from Harper Ferry. This made an infantry assault unlikely. Miles had to defend Bolivar Heights. Jackson was positioned at the western base of Bolivar Heights on a rise known as Schoolhouse Ridge. Miles has an advantage since his position was two hundred feet higher than Schoolhouse Ridge. Miles held the high ground. [13]

Schoolhouse Ridge – Jackson’s force massed on this ridgeline at Harpers Ferry (P. Chacalos)

On September 14, Jackson ordered his guns on Maryland Heights and Loudon Heights to commence firing. Despite the constant shelling, Miles STILL refused to surrender.[14] At this point, Jackson realized he MUST attack, and he planned a frontal assault for that night. While his troops demonstrated on the front, Jackson sent General A. P. Hill on a flanking movement from the southern edge of Schoolhouse Ridge. At the same time, Jackson ordered ten guns to be redeployed to the base of Loudon Heights. Hill moved south to the Shenandoah River. He then moved along the river to the Chambers Farm on the lowest part of Bolivar Heights. Hill was now behind the Federals. The frontal assault was a fake. Hill’s movement was the actual attack. Hill placed his artillery on the Chambers farm. Miles was oblivious to these maneuvers, and the Battle of Harpers Ferry had been decided.[15]

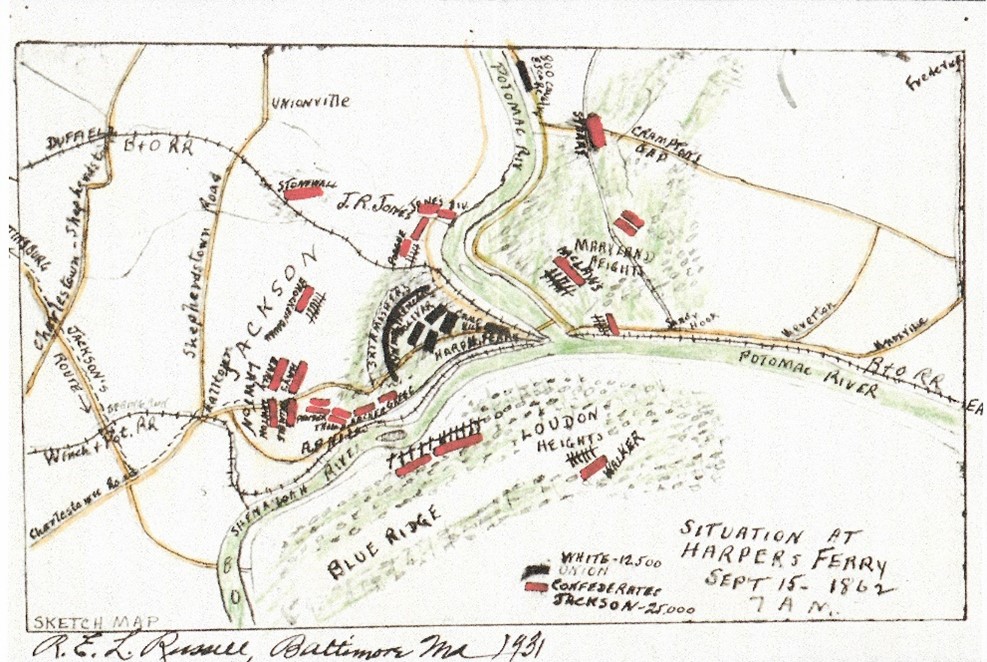

The disposition of forces on the morning of September 15, 1862 (LOC)

Surrender

As the morning dawned, Harpers Ferry was shrouded in a heavy fog.[16] Colonel Miles observed A. P. Hill to his rear as the fog began to lift. The batteries at the base of Loudon Heights soon opened fire as those on Schoolhouse Ridge attacked from the front. The guns commanded by Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield opened from the rear as the batteries of Captains Pogue, and Carpenter opened on the Federal right. In addition, McLaw’s artillery commenced firing from Maryland Heights.[17] Surrounded, outnumbered, and out of long-range artillery ammunition, the situation was hopeless. Miles called a council of war with his brigade commanders. The decision was made, reluctantly, to surrender. Miles was mortally wounded when a Confederate shell exploded near him as the white flag was raised. [18]

The Aftermath

Jackson sent word to Lee of the Harpers Ferry surrender and moved with his forces to reunite with Lee behind Antietam Creek near Sharpsburg. A. P. Hill’s division was left to accept the surrender of Harpers Ferry.[19] With Miles mortally wounded, the garrison was surrendered by Brigadier General Julius White. The Federals were granted liberal terms. The officers and men were paroled, and the officers could keep their sidearms. Wagons were loaned so the officers could take their personal belongings with them. [20]

The final cost to the federal troops, as indicated in Jackson’s after-action report to the Adjutant General, follows:

COLONEL: Yesterday, God Crowned our army with another brilliant success in the surrender at Harpers Ferry of Brigadier General White and 11,000 troops, an equal number of small arms, 73 pieces of artillery, and about 200 wagons. In addition to other stores, there is a large amount of camp and garrison equipage. Our loss was minimal. The meritorious conduct of officers and men will be mentioned in a more extended report.

I am, colonel, your obedient servant,

T. J. Jackson,

Major General[21]

The Aftermath

General White requested a court of inquiry to determine if the surrender was justifiable. He cited the terrain of Harpers Ferry and its surroundings as a significant factor. White indicated there were just not enough men to hold the three heights surrounding Harpers Ferry. The results of the inquiry are summarized below:

- The committee found nothing in the conduct of subordinate officers (except for Colonel Ford) that was any cause for censure.

- General White acted with capability and with courage.

- Due to the disgraceful behavior of the One hundred twenty-sixth New York Infantry, commanding office Major Baird should be dismissed from the service

- The force on Maryland Heights was not appropriately managed.

- The abandonment of the heights was premature

- The guns abandoned were not spiked and thrown down from the heights

- Colonel Ford should not have been placed in command and did not have the ability to command the army.

Due to the death of Colonel Miles, the committee was reluctant to consider his case. However, the evidence convinced the committee that “Colonel Miles’ incapacity, amounting to almost imbecility, led to the shameful surrender of this post.” [22]

Jackson and Lee

With the fall of Harpers Ferry, Lee’s rear was no longer threatened. However, McClellan was in front of Lee at South Mountain and headed toward Sharpsburg. With two-thirds of the army, Jackson immediately moved to rejoin Lee behind Antietam Creek, arriving in time to engage the Army of the Potomac on September 17, 1862, in the Battle of Antietam, the single bloodiest day in American history. After paroling the Harpers Ferry garrison, A. P. Hill arrived at Sharpsburg late on the seventeenth, saving Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia from almost certain disaster. If not for the Battle of Harpers Ferry, the Battle of Antietam would probably never have happened. Lee would have passed through Maryland and into Pennsylvania. From that point, what would have occurred is left only to speculation.

Each side was left licking its wounds the day following the Battle of Antietam. On that day, Lee, not liking his position with the river to his rear, decided on a movement back to Virginia. That evening, under the cover of darkness, Lee slipped away from Sharpsburg and headed for the Boteler’s Ford crossing near Shepherdstown. This movement, however, was not a retreat. Lee fully intended to continue the campaign into Pennsylvania. After crossing at Boteler’s Ford, Lee intended to move upriver and re-cross into Maryland at Williamsport. Lee sent J.E.B. Stuart and his cavalry to Williamsport to secure this crossing. [23]

[1] American Battlefield Trust, The Battle of Harpers Ferry: 158th Anniversary of Antietam Live! YouTube 29:04, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=97KZ0WEqGyo

[3] Ibid

[4] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I Vol. 19, Ch. 31, Reports of General Robert E. Lee, C. S. Army, pp. 139-153

[5] Earl J. Hess, The Terrain and Fortifications of Harpers Ferry, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/terrain-and-fortifications-harpers-ferry

[6] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I Vol. 19, Ch. 31, Report of Col. Thomas H. Ford, Thirty-second Ohio Infantry, commanding brigade, of action on Maryland Heights, pp. 541-544

[7] Ibid

[8] Ibid

[9] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I Vol. 19, Ch. 31, Reports of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, C. 8. Army, pp. 852-857

[10] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I Vol. 19, Ch. 31, Report of Col. Thomas H. Ford, Thirty-second Ohio Infantry, commanding brigade, of action on Maryland Heights, pp. 541-544

[11] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I Vol. 19, Ch. 31, Reports of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, C. 8. Army, pp. 852-857

[12] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I Vol. 19, Ch. 31, Report of Brig. Gen. John G. Wallace, C. S. Army, pp. 912-614

[13] Dennis Frye, Stonewall Jackson’s Triumph at Harpers Ferry, for Hallowed Ground, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/stonewall-jacksons-triumph-harpers-ferry

[14] Ibid

[15] Ibid

[16] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I Vol. 19, Ch. 31, Reports of Brigadier General John G. Walker, C. 8. Army, pp. 912-914

[17] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I Vol. 19, Ch. 31, Reports of Lt. General Thomas J. Jackson, C. 8. Army, pp. 951-958

[18] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I Vol. 19, Ch. 31, Reports of Brigadier General Julius White, U. S. Army, pp. 523-530

[19] Overview, The Battle of Harpers Ferry, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/harpers-ferry

[20] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I Vol. 19, Ch. 31, Reports of Major General Ambrose P. Hill, C. 8. Army, pp. 979-982

[21] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I Vol. 19, Ch. 31, Reports of Lt. General Thomas J. Jackson, C. 8. Army, pp. 951-958

[22] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Ser. I Vol. 19, Ch. 31, Record of the Harpers Ferry Military Commission., pp. 549-800

[23] Antietam leading to The Battle of Shepherdstown: Antietam 158, American Battlefield Trust, YouTube, 20:30, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7R76JRMPMY